by Ron Anahaw

Jfc, what a wild movie to casually watch on a Wednesday evening.

The movie opens with an amazing visual sequence: we see only a man’s shadow as he continuously leaps in the middle of the desert, reaching higher and going farther each time. We don’t know who the man is, where he is, or why he’s doing this. We can only see how high his view goes.

Bardo: A False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths is Alejandro González Iñárritu’s latest film, marking seven years since his 2015 film The Revenant. You may also know him for his 2014 film The Birdman (one of my favorite movies).

Bardo could be described as a meta, poetic, philosophical portrait of a man whose career is pursuing truth while his life is destabilized by his own mythology. Or it could be described as a collection of vignettes bound together by magical realism and imposter syndrome. There are lots of fancy ways to describe what Iñárritu’s done here, for better or worse.

We follow Silverio Gama, a recently acclaimed journalist whose career is finally on the rise. He’s set to be the first Mexican to be awarded a prestigious journalist prize by the Academy of American Journalists. People have drawn the parallels between Silverio and Iñárritu, but I don’t recall if Iñárritu ever directly stated the connection. Either way, the parallels are there. Silverio’s acclaimed work is also titled Bardo: A False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths and its critics decry it for bending the truth, while Silverio defensively states that it’s “docufiction.”

There’s a lot to unpack. Let’s start with the magical realism. Whenever reality is disrupted in the movie, it’s breathtaking. Lucía, Silverio’s partner, gives birth to a newborn who promptly requests to stay inside his mother because “the world’s too fucked up.” So the doctors put the baby back inside. If you’re as clueless as I am, the movie clearly later spells out how this represents how Silverio and Lucia’s child died shortly after its birth.

Hernan Cortes awaits Silverio atop a pile of indigenous corpses. Three axolotls wade around in ankle-high water inside a bus, which leaks out into Silverio’s apartment in the desert. Silverio speaks entire monologues without moving his mouth. He reconciles with his dead mother and father. For some reason, through all of it, it felt like Silverio had some degree of…control? Like he was willing reality to disrupt in these ways. Perhaps because the movie primes us to perceive Silverio as Iñárritu, so he is simultaneously protagonist and director.

The truth is, there is no such control to it. But more on that later.

Daniel Giménez Cacho gives an astoundingly impressive performance as Silverio. He lives and breathes Silverio in all his holier-than-thou, pro-and-anti-Mexico, imposter syndrome-d, romantic, family man-ness. Similarly, all the members of Silverio’s family are gifted with intimately convincing performances: Griselda Siciliani as Lucía, Ximena Lamadrid as their daughter Camila, and Iker Sanchez Solano as Lorenzo. Theirs is a family whose love, though far from perfect, feels real and tangible. There’s mess, but there’s warmth.

In its simplest, you can divide the film into two aspects: Silverio’s personal and professional lives. His personal life of wrestling with his insecurity, bridging the gaps in his family, and repairing broken friendships in Mexico. And his professional life of feeling like an imposter despite winning an incredible accolade.

But the film’s execution prolongs this across a wieldy 2 hours and 40 minutes. It had me in the beginning, lost me in the middle, and impressively got me–like, really got me–in the last thirty minutes.

Biggest spoiler alert in the review: all of Silverio’s fantastical experiences so far are representing his brain activity after he has a stroke and falls into a coma. The wildest part is you get these hints very strongly in the first twenty minutes of the movie, you just don’t put it together (or at least, I didn’t) until the end.

There is a beautiful sequence where Silverio wanders the desert and sees so many of his loved ones, friends, and peers beckoning to him as he navigates the sandy terrain. Before the end, he hears his wife and two children beg for them to join him. He insists that they can’t come with him, there’s nothing for them where he’s going.

Then we return to the shot at the beginning, and wonder to ourselves if Silverio flies off to some afterlife, or awakens back to his family. Either way, the film did a beautiful job of piecing together the imperfect parts of an imperfect man’s life.

SCORE: 95/120

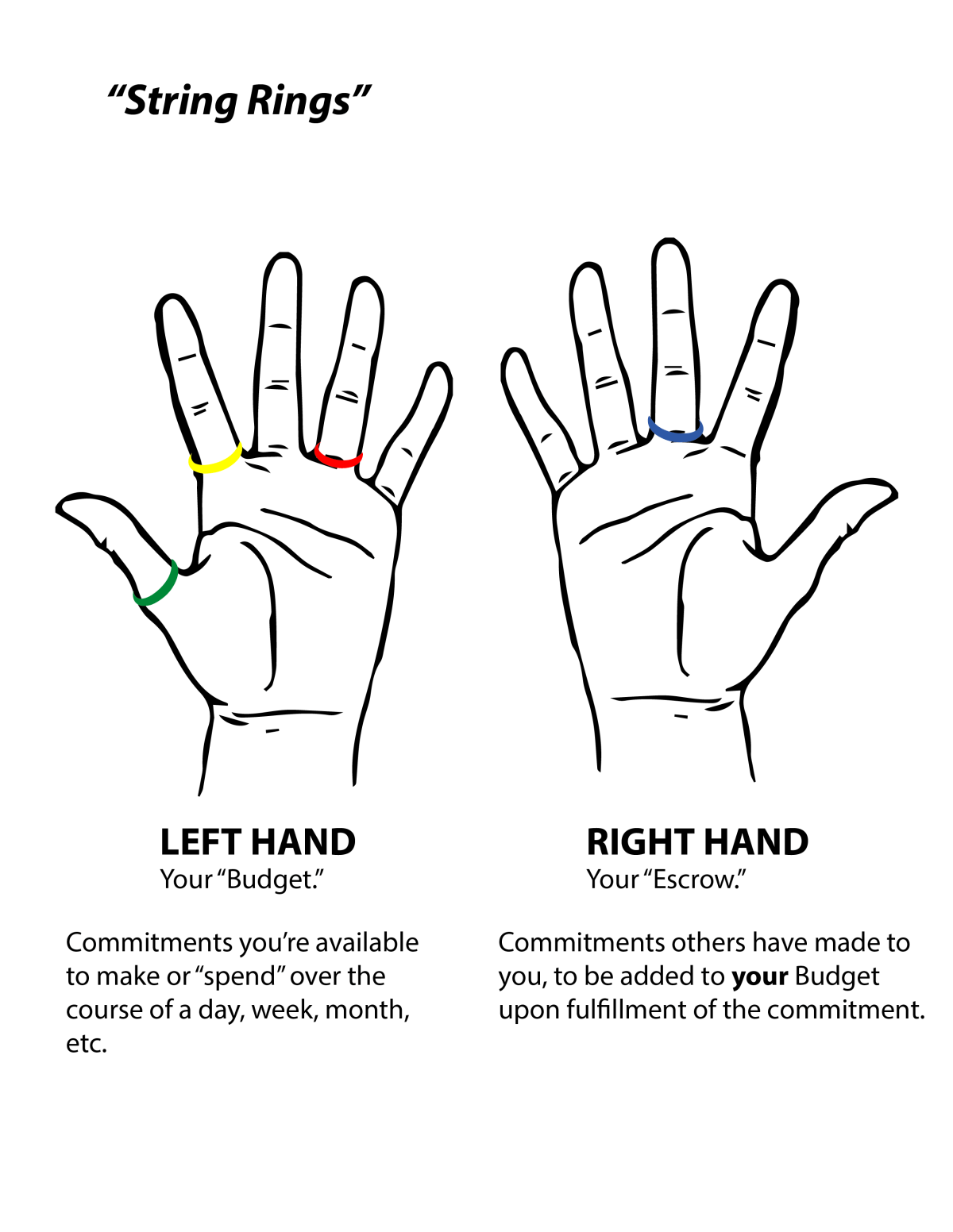

| Enjoyment | Emotion | Aesthetic | Narrative |

| 7 | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| Cohesion | Originality | Execution | Impact |

| 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Ending | Rewatchability | Recommendability | Staying Power |

| 9 | 7 | 7 | 9 |